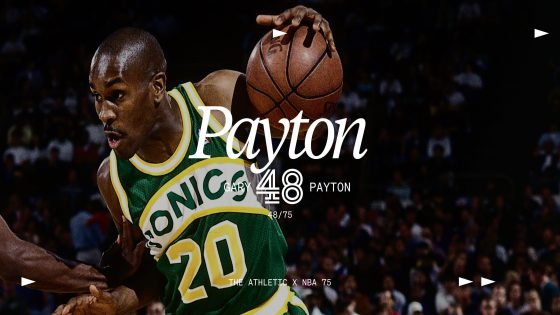

Welcome to the NBA 75, The Athletic’s countdown of the 75 best players in NBA history, in honor of the league’s diamond anniversary. From Nov. 1 through Feb. 18, we’ll unveil a new player on the list every weekday except for Dec. 27-31, culminating with the man picked by a panel of The Athletic NBA staff members as the greatest of all time.

Gary Payton was rarely quiet on the basketball court during his Hall of Fame career. He was big loud — both with this game and with his mouth. His bellowing and his cackling echoed throughout the arenas around the NBA. Didn’t matter if you had just scored on him, or if he shut you down from even thinking about trying to score.

That’s why on Feb. 17, 1999, it was so shocking to see Payton momentarily silenced by a rookie. “GP” was on his way to a sixth consecutive NBA All-Defensive First Team selection when Jason Williams and the Sacramento Kings came to town. Williams hit Payton with a moment that just left the Oakland product with a big grin on his face.

The Jason Williams experience in Sacramento was in full swing. Williams, a rookie, was part of a Kings revival that hadn’t happened since Oscar Robertson was laying the cobblestones in Cincinnati for Russell Westbrook to traverse. The Kings were fun because of Chris Webber and Vlade Divac, but they were electrifying because of Williams.

So, just seven games into his career, Williams found himself in Seattle. A couple minutes into the game, Detlef Schrempf lost the ball around the left elbow while battling Corliss Williamson. Williams sprang into action, pouncing on the loose ball and heading the other way. He dribbled quickly up the right side, as Schrempf and Payton retreated to cut off the rookie point guard. But Williams brought the ball up the floor too quickly and didn’t have numbers. He was waiting for teammates to run down the court to give the Kings the advantage in transition. So, he slowed and surveyed what he had in front of him.

The surveying of the floor, however, was a ruse. Williams brought the ball from his right hand to his left hand by going between his legs. His left hand cradled the rock as the defender in front of him brought his heels down to the court to find a better position. Williams turned his body quickly from the middle of the floor toward the baseline. He brought the ball from the left to right. The defender stuck a foot out briefly in a half-footed attempt at a possible trip and reached with the left hand, but conceded that he had been fooled.

The three-part magic trick saw the prestige as a high runner off the glass from Williams. Everybody was amazed from the play, and while the crossover was good, it was the victim of the crossover who made the play memorable.

Williams had bested Payton —”The Glove” — who was a couple of seasons removed from being one of five guards in NBA history to win Defensive Player of the Year (1996). He was the NBA’s gold standard for defensive guards, and defense in general, and lands at No. 48 on The Athletic’s NBA 75. And yet in one brief moment, Williams had just taken it to him, announcing his arrival to the NBA and seeming to say: “If I can get Payton, I can get anybody.” That’s all it took to show you he meant business on the court. Have one highlight against GP, and you were legitimized as a weapon.

Payton was as confident as any defender has ever been. And ever will be. Both on the inside and out. He was so confident that in the moments following the fake and score by Williams, he just smiled at the rookie. It wasn’t a rude or mocking smile. It wasn’t one of those smile versions of a sarcastic clap. Payton seemed tickled by the moment. He walked up the court and smiled right at Williams, appreciative that the rookie guard was competing against him. Instead of looking for an excuse as to why he got tricked and nearly tripped an opponent, it forced Payton to be even more competitive.

Here’s a sight few, if any, opposing guards wanted to see: Gary Payton in a defensive stance. (Rocky Widner / NBAE via Getty Images)

Not many players’ highlight reels included Payton. Not many even wanted to try. As stellar as it was, Payton didn’t just have a defensive reputation. The Glove talked constantly to take a player out of his game. The trash-talking itself was absurdly versatile. He’d come for your throat, your heart, your funny bone. Opponents talked about how relentless Payton’s trash talk would be, and it never discriminated. It never took a night off. He never stopped jawing at opponents, breaking them as much psychologically as he would physically.

Hall of Famer Grant Hill credits Payton with starting him off as becoming a point forward in the NBA because Hill’s point guard teammate at the time didn’t want to bring the ball up against The Glove. Hill took the assignment as Payton stalked from the help side, and Hill showed a knack for being a playmaker. It stuck as an eventual role for Hill, thanks to Payton just being a pain in the ass to dribble against.

Kenny Smith once mentioned on “Inside the NBA” on TNT that having played Payton a few times in the postseason, Payton talked as much trash to his own teammates — if not more — as opposed to his opponents. Payton would scream to get him the ball because he couldn’t be guarded by his assignment. He yapped in practice to help drive home the points and the game plans of his coaches. He also did it to motivate himself to perform on a nightly basis. There was a madness to the tornado of words that ravaged the eardrums of those in front of him.

“It made you want to get back at him even more,” Hall of Fame forward Chris Mullin once said about Payton, “but ultimately, the real frustration came from how great a player he was. Backing it up, that’s when trash-talking goes to another level. If you trash talk and you can’t back it up, you’re just a clown.”

You never saw paint on Payton’s face or a big red nose. Payton was the embodiment of psychological warfare on the court. His defensive prowess could not be discounted in any way because it was the way he bullied anybody thinking about scoring against him. That’s what set him apart. He was as strong as most big men and knew how to use leverage and hand strength to keep opposing players frustrated. He calculated angles in the blink of an eye, and his crystal ball of where you wanted to take the ball was clearer than the most well-constructed window. When he stopped you, you heard about it. When he didn’t stop you, you heard about how that wasn’t going to happen again.

“First time we met, we’re playing in Seattle,” Hall of Fame point guard Isiah Thomas once recalled in a TV discussion involving Payton himself. “I catch the basketball, and all I hear is, ‘(unintelligible sound).’ I can’t repeat what he was saying. And I’m holding the basketball, and I’m looking at him. And then I had to turn around, and I was like, ‘Is he really talking to me?’ He was talking so much trash.”

“Hey, I had to do it,” Payton interjected. “I had to.”

“I didn’t know him though!” Thomas said.

“He didn’t even know who I was,” Payton explained.

“I stopped for about five seconds,” Thomas continued. “Game was going on, I was dribbling the ball, and he was talking. I picked up the ball just to, like, look at him.”

That was Payton’s second career game during his rookie season. Thomas and the Detroit Pistons, fresh off back-to-back championships, went into Seattle to play an up-and-coming Sonics team. Shawn Kemp wasn’t even starting at that point; he was coming off the bench. That’s how green the Sonics were as they were putting together their core for the future. It didn’t matter that Payton didn’t even have his feet wet in the NBA. It didn’t matter that Thomas and the Pistons were two-time defending NBA champions. Payton was there to talk. He was there to defend. And he was there to compete.

The Sonics won that game by eight points. Payton had a modest performance of nine points, six assists and three steals in 31 minutes. He helped hold Thomas, the reigning Finals MVP, to 10 points, going 3-for-13 from the field, with five assists and five turnovers. He didn’t just catch Thomas off-guard with his constant yapping. He showed that everybody was going to have to bring it against him, or they were going to hear about it.

Let’s be honest. They were going to hear about it even if they did.

“I played with GP, and I played against GP,” Hall of Fame center Shaquille O’Neal said about Payton when naming him the best trash talker on an episode of “Open Run” on NBA TV years ago. “He just didn’t care. The crazy thing about GP on the court is he was like that off the court. If he saw you in the mall: ‘Remember that time I crossed you up, big fella? And I gave you that thang with the left hand? And you went up to get it and almost pulled your arm out of your socket? I’m a Hall of Famer! I’m first ballot, boy!’”

Payton was an easy selection for the Hall of Fame. Somebody who didn’t need any discourse about whether it would be deserved. Payton’s peers have never questioned whether he belongs. It wasn’t just his defensive reputation, either. There have been plenty of great defensive players who will never even sniff the Hall of Fame. Payton got right in because he was an all-around player.

He was a brilliant leader on offense, not only known for finding running mate Shawn Kemp for eye-popping alley-oops but also for being surgical in how he dissected a halfcourt set to find his team’s best scoring option. Payton had a 10-year run from 1993 through the 2002-03 season in which he averaged 20.1 points, 7.9 assists, 4.5 rebounds and 2.1 steals while making 46.8 percent of his shots. He made nine All-Star games during that 10-year period. He made nine All-NBA teams during that stretch with two First Team appearances and five of them landing him on the Second Team.

Payton is currently 10th all-time in total assists, and he sits fourth in total steals. When he retired in 2007, Payton was sixth in assists and third in steals all-time. Only John Stockton, Mark Jackson, Magic Johnson, Oscar Robertson and Thomas were ahead of him in assists. Only Stockton and Michael Jordan were ahead of him in steals. When he retired in 2007, he was also just outside the top 20 in all-time points at No. 21 — fewer than 400 points behind Clyde Drexler and 22 points ahead of Larry Bird.

The Glove eventually got his validation with a championship. In one of the most surprising NBA Finals results in history, he missed out on one in 2004 when he teamed up with Shaq, Kobe Bryant and Karl Malone on the Lakers. But two years later, he bounced back with Shaq and Dwyane Wade to help give the Miami Heat their first championship. He wasn’t a top contributor in that series, but his jumper at the end of Game 3 against Dallas kept the Heat from going down 3-0 in the series. And, as they secured the title, they trusted him to play defense in the closing minutes of Game 6.

On his third trip to the NBA Finals, Payton finally got his ring, with the Miami Heat in 2006. (Jesse D. Garrabrant / NBAE via Getty Images)

He was the man unafraid to take it to Thomas and tell him about it when nobody really knew who Payton was. He was the man assigned to defend Jordan with his Sonics down 3-0 in the 1996 NBA Finals against the 72-win Chicago Bulls. The Sonics would eventually fall in six games to Jordan and the Bulls, but Payton helped hold Jordan to the worst NBA Finals field-goal percentage (41.6) of his career. Payton was the guy there to make life hell, tell you all about it and refuse to discriminate between his friends and strangers in the league. He was as tough as they came, being a product of Al “Mr. Mean” Payton and his upbringing in Oakland, Calif.

“The strength of his game is defense and toughness,” Jalen Rose recalled in an interview when talking about his Payton talking trash to him on the floor. “He talks a lot of trash. And he’s willing to fight you. Right? What you gonna do with that?”

According to John Salley, Payton is a “hater.” But Salley said the difference between Payton and a lot of trash talkers is it wasn’t just him posting up Thomas as a rookie and screaming to the Pistons they better bring help against him. It wasn’t just about Payton saying he didn’t care what was said about you in the newspaper because to him, you weren’t anything. Salley has said with Payton, he’ll make you believe it.

Hall of Famer and fellow Oakland product Jason Kidd credits Payton with showing him how hard you need to work to be great. He also credits Payton with toughening him up. He’d belittle Kidd in their workouts to see if Kidd would come back the next day for more work. That’s where Payton’s competitiveness reverberates throughout history.

Williams got him once, and Payton embraced it because he appreciated someone not being afraid to go against him. Kidd kept coming back to work with Payton despite the trash talk because it made him better.

Payton loved that fight. He didn’t bully people on the court physically and verbally to diminish them. He did it to bring that fight out of them. He was there for it all. Make a move against him, and be immortalized. That’s how good he was. That’s how overwhelming he was. That’s how loud he was. His game will echo throughout the history of this league, no matter how long the NBA goes. And it will only be just a tiny decibel louder than his mouth.

Career stats: G: 1,335, Pts.: 16.3, Reb.: 3.9, Ast.: 6.7, FG%: 46.6, FT%: 72.9, Win Shares: 145.5, PER: 18.9

The Athletic NBA 75 Panel points: 406 | Hollinger GOAT Points*: 149.5

Achievements: Nine-time All NBA, Nine-time All-Star, Defensive Player of the Year (’96), Steals champ (’96), NBA champion (’06), Olympic gold (’96, ’00), NBA 75th Anniversary team (’21)

*A rating of a player’s accumulated accomplishments at the highest levels, based mostly on comparable historical factors, determined heavily but not completely by contemporary evaluations (i.e. awards and All-Star selections). Emphasis is given to the most outstanding achievements — MVP award shares, All-NBA teams, and production above and beyond what is typically an All-Star level.

(Illustration: Wes McCabe / The Athletic; Photo: Rocky Widner / NBAE via Getty Images)