Athens, Greece – Frustration with the United States for holding back critical financial and military aid from Ukraine spilled into the open at the Delphi Economic Forum in Greece last week.

“The Russians are destroying Ukrainian power plants, which is a war crime, but unfortunately they’re getting away with it because as the collective West we have not supplied Ukraine with enough missiles,” Radoslaw Sikorski, the Polish former foreign and defence minister, told Al Jazeera on the sidelines of the meeting.

On the day he spoke to Al Jazeera, Russia unleashed a barrage of some 80 missiles that completely destroyed a thermal power plant in Kyiv, which supposedly has the best air defences in the country.

It was only the second time in the war that an entire electricity plant had been destroyed. Russia destroyed a plant in Kharkiv on March 24.

“You can’t run modern cities without electricity. So I’m afraid that by not giving Ukrainians enough anti-aircraft or anti-missile effectors in time, we may be getting another wave of refugees who can’t stay in their own cities,” said Sikorski.

Poland is already home to almost a million Ukrainian refugees out of a total of six million in Europe.

Meanwhile, Republicans loyal to presidential hopeful Donald Trump in the US House of Representatives have been afraid to defy him by voting for a $60.1bn package of aid stuck since December – despite the fact that Democrats and Republicans in the Senate have approved the bill. One commentator said he was “optimistic” it would now pass.

“We are beyond primary season, in which members of Congress that might vote on hot button issues the wrong way for parts of their constituency get primaried by people, particularly from the right,” said Charles Ries, a senior fellow at the RAND Corporation, a US think tank.

“I’ve been hearing this ‘by next week’ or ‘by next month’ for about eight months so I’ll believe it when it happens,” said Sikorski.

There was also frustration that Europe’s defence industry had been slow to ramp up munitions production and fill the gap left by the US.

“They are not producing enough even for themselves,” Ukrainian MP Yulia Klymenko told Al Jazeera. “For two years they have talked about how maybe tomorrow or by the end of 2025 they will start production. It is looking very irresponsible.”

“What the war in Ukraine showed was that … the depletion rate for munitions is much faster than we had planned beforehand, so we need to rearm ourselves as well as Ukraine. We need to beef up our military-industrial capability,” David Lidington, chair of the Royal United Services Institute, a London-based think tank, told Al Jazeera.

Sikorski estimated that Europe had actually delivered the one million artillery shells it promised Ukraine a year ago, in money or kind.

A separate Czech initiative to buy stockpiled shells from around the world would deliver about another million by June, he said, when a new Russian offensive is expected.

“But compare this to the Russian production of 2-3 million [a year],” he said. “We have many times their resources but they have mobilised their resources better.”

European Union members have also committed to predictable, multi-annual financial and military assistance to Ukraine.

‘Ridiculous excuses’

Still, there was frustration with Germany for not supplying Taurus missiles with a 500km (310-mile) range, fearing they would be used to strike Russia, and the US administration of Joe Biden for not supplying 300km-range (186-mile) Army Tactical Missiles (ATACMs).

“I’m sure Russia does not have the ability to knock Ukraine out of this war. They’re banking on us failing to deliver what’s needed and almost winning by default,” said Ben Hodges, a former commander of US forces in Europe. “Get rid of all these ridiculous excuses about why we can’t provide certain kinds of weapons.”

Much of the frustration with Europe focused on its perceived lack of perspective on the scale of the challenge. For example, European financial institutions hold more than $200bn in Russian assets, but while the EU has decided to funnel about $3.5bn in proceeds from investing that money to Ukraine, it has yet to decide on touching the principal.

Klymenko blamed the European Commission, the EU’s executive, for focusing too much on keeping Ukrainian agricultural imports out of the EU.

“They don’t realise that they are next in line. It’s like kids playing with fire and they don’t realise this fire will burn their house,” said Klymenko, referring to fears of a Russian attack on NATO in coming years.

But the reality of what was at stake was beginning to dawn on Europeans, said Hryhoriy Nemyria, a deputy chairman of Ukraine’s parliament.

“What we are understanding better and better is that this [military] help is not a charity. It’s because, we believe, it is in the naked self-interest of those countries who are providing this help and now are considering doubling down on it,” Nemyria told Al Jazeera.

That realisation comes not a moment too soon, he said.

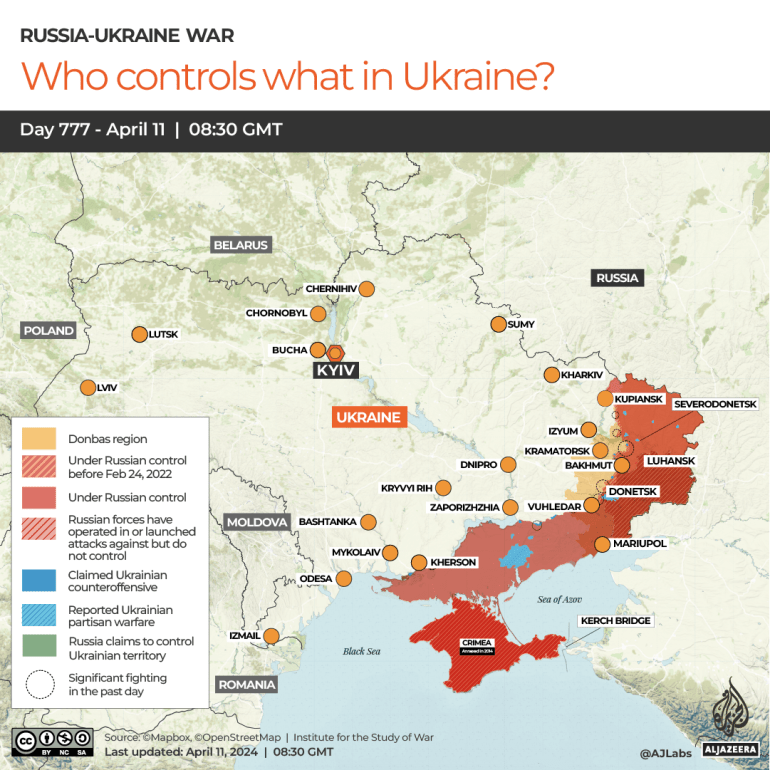

Ukraine has been suffering a shortage of weapons since last summer when it mounted a counteroffensive against well-prepared Russian positions and failed to breach them. Nine months earlier, it had routed Russian forces in a counteroffensive that took back much of Kharkiv in the north and Kherson in the south.

The Kiel Institute for the World Economy, a German think tank, estimated that weapons commitments from Ukraine’s allies in August-October last year were 87 percent lower than during the same period in 2022, suggesting complacency as a result of early success.

“We need to finally come up with the high-precision long-range weaponry, de-mining equipment … and artillery shells to breach the front. There is still time to do this,” said Nemyria.

Despite the inconstancy of its allies, Ukraine continues to mobilise the one resource for which it is still solely responsible: manpower.

Last week it passed its third mobilisation law since 2014, when its war against pro-Russian separatists began in the east. It aims to raise up to 300,000 new troops, bringing its armed forces to a total of 1.2 million men and women in uniform by the end of the year.

The extra troops represent six times the manpower it raised for last year’s counteroffensive, but it needs commitments from allies to equip these forces, which means its demands will only grow.

Nemyria is optimistic about Ukraine’s prospects.

Two years ago, he said, “it was quite strange speaking in European capitals and trying to convince your interlocutors that Ukraine is a European nation.”

Ukraine has proven its commitment to Europe and paid for it in blood. That, he said, meant that Ukraine was being reborn as a European nation, and the EU and Ukraine were bound together in both victory and defeat.

“Every nation in history has this moment of truth,” he said, “to prove that you are a real nation that deserves freedom or not.”